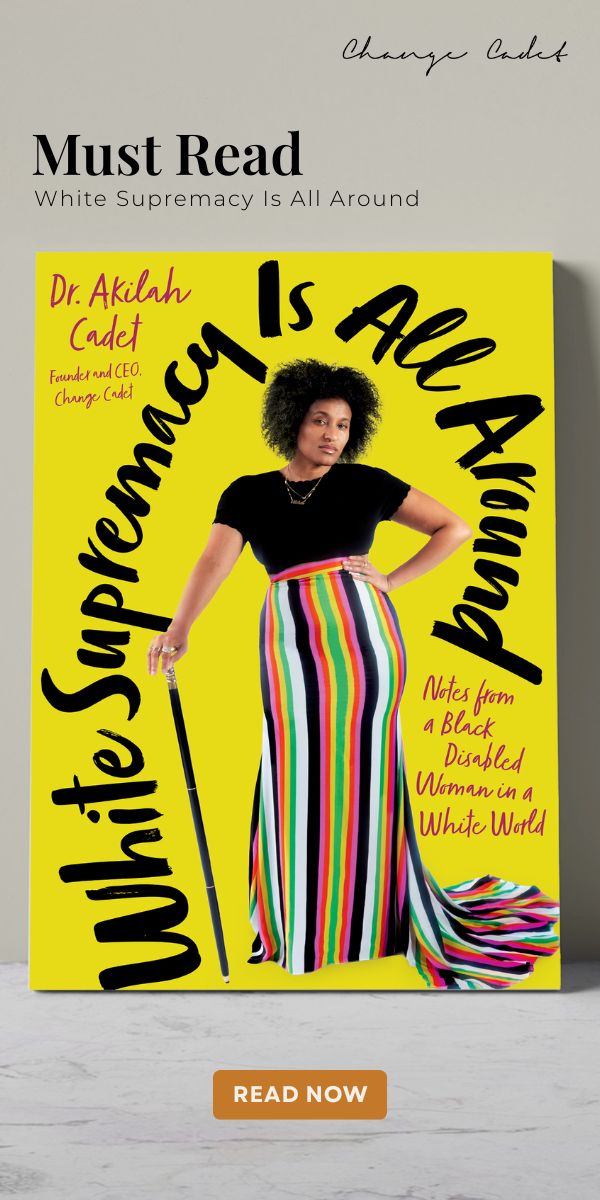

Before the read

He weaves together broken ceramics and fabric strips to tell stories of healing, identity, and resistance.

His work blends crochet, ceramics, and tradition into participatory art that reflects both personal history and collective liberation.

O’Arwisters believes it can—especially when creativity is shared in safe, judgment-free spaces like his Crochet Jams.

Black and Queer Crocheter and Sculptor Ramekon O’Arwisters Celebrates Heritage and Community Through Healing Crafts Experiences

Queer, Black sculptor and crochet artist Ramekon O’Arwisters describes his style as liberating, grounded, and authentic.

“I feel most grounded and affirmed when I focus on my creativity. I can absolutely trust my creativity; it only requires that I remain fearless and authentic in my creative vision,” he says.

Hiding Within His Early Art

It hasn’t always been easy for O’Arwisters to accept and share all of who he is. Growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, he used drawing and painting to hide his queer feelings and thoughts.

“It was a way for me to keep my parents from knowing about me being queer since I knew they would not approve. To keep them from asking why I wasn’t interested in masculine activities such as sports or dating girls, I kept busy doing art and homework on the kitchen table,” he says.

He now reflects that his parents were likely glad he was safe at home and not out messing around with drugs or fighting or at risk of getting arrested. “In Black America at that time, parents of little Black boys feared for them, especially from the brutality of the police,” O’Arwisters says.

His artwork then was mostly geometric shapes and patterns. “My drawings had no content. They were void, empty, dull, but pretty.”

Improvising with Colorful Remnants

Now, O’Arwisters sculpts with broken ceramics and strips of remnant fabric with a clear intention. “These are marginalized materials, objects that are thrown away, detritus. We treat them the same way that American culture treats marginalized people. They are ignored, abused, and disposable. I use these materials as stand-ins for the disposable experience of humans who are disenfranchised within the myth, or better, the lie of the American Dream.”

O’Arwisters has observed that the art-world system was designed to confirm and maintain the status quo rather than to support Black artists.

“For the majority of my art career, I have been relinquishing my agency over and over again whenever I go to figures of power in the white art world—curators, gallery directors, museum directors—to present to them my work and ask for their approval. Is my work good? Is it worthy of your gallery? Am I good enough?”

Realizing this process was no longer working for him, O’Arwisters stopped presenting his work to anyone for a while.

“I needed time to reflect, to sit back and re-evaluate, to stop doing the same things and expecting different results. My mother and especially my grandmother made quilts. Contrasting colors and improvisation made their creations like jazz, reflecting the necessity in Black life in the United States to use color to lift the spirits in a hostile environment and to use improvisation to solve problems and situations in a world where opportunities are limited, kept out of reach due to the evils of racism,” he says.

This gave him the idea to turn his personal and cultural heritage of quilting and sewing into a public art-making practice.

Passing on a Childhood Gift

The popular community art event he hosts, the Crochet Jam, is rooted in cherished childhood memories steeped in the African-American tradition of weaving together in a calm, non-judgmental environment without rules or limitations.

“My mother and grandmother expressed their worldviews and emotions through textile and fabric,” he remembers. His mother was a piecemeal textile worker at Hanes Knit, then located in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. She worked long hours sewing sleeves onto t-shirts and taught O’Arwisters how to operate a sewing machine.

“At a young age, I learned from her how to thread the machine, how to sew on a button, how to do single-stitch sewing, and other techniques,” he says.

His grandmother was a quilt maker who crafted beautiful quilts for him and his siblings, including one they could take for their beds when they left for college.

“She lived next door to us, and one day I visited her, and she was sitting on the bed, quilting. As I came into the bedroom, she turned toward me and said, ‘Boy, come over here and help me with this quilt.’”

The last thing O’Arwisters wanted to do that day, he remembers, was some kind of craft project that would make him question his masculinity. “I was already at an age where I was becoming aware of my same-sex attraction,” he says. “Quilting and sewing had made me suspect, afraid, and withdrawn, and I contemplated all of this as I walked towards her. But expressing my displeasure with my grandmother’s request would have been a serious mistake.”

His grandmother calmly looked at him and said, “Pick any color or pattern you like, and I will show you how to add it to my quilt.” She’d already invested months of work into building an intricate pattern, which she was allowing him to break.

“My grandmother knew I was struggling with something—my sexual identity, homophobia, and White-body supremacy. She intuited that I needed to feel embraced, accepted, and heard. We did not talk much. She taught me how to quilt pretty much in silence. She never told my parents. It was just the two of us. It was the most loving act,” O’Arwisters remembers.

This kindness made a deep impact on him during a very difficult time to be Black and queer. In the U.S., Jim Crow segregation was the law of the land, and he remembers watching movies on the balcony of his hometown’s theater because it was illegal for Black people to enter the lobby. Homophobia was just as rampant and socially acceptable.

O’Arwisters remembers that at this time, Black people were redefining themselves as strong individuals worthy of respect and equality. He decided to help create an environment of non-judgmental acceptance with his Crochet Jams to give others what his grandmother gave him.

“It is my family legacy in remembrance of her,” he says.

Public Art Creation as a Space for Social Liberation

What O’Arwisters remembers most from the many Crochet Jams he’s hosted is not so much what the people created but how people reacted to the experience.

“When individuals feel comfortable and not judged, they will discuss many personal issues they would never discuss in public—abortion, divorce, unhappiness,” he says.

He remembers one particular event in Asbury Park, NJ where a man stood and stared at the people gathered around large piles of colorful fabric. Finally, he walked over and asked what was happening.

“Welcome to Crochet Jam!” O’Arwisters said. “It’s a free public event in which we use the folk-art tradition of crocheting strips of fabric to foster social interaction, liberation, and creativity.”

The man joined, crocheted for a while, and then started helping others and showing them how to single-stitch crochet. Before he left, he said goodbye to his new friends. Then he walked over to O’Arwisters.

“My father died a few days ago, and I had nowhere to go. Thank you for being here,” he said, leaving O’Arwisters speechless.

O’Arwisters reflects on how humans carry a great deal of pain and fear and hope that community art events of this nature help ease that.

In this way, he can work toward community liberation, creating a world where all people can live and be respected as their true selves.

His current exhibitions include A Chorus of Twisted Threads at the Patricia Sweetow Gallery, Freeform and Razor Sharp at San Francisco’s Museum of the African Diaspora, and Fight and Flight at the Museum of Craft and Design.

More by this author

The Wrap

- Ramekon O’Arwisters is a Black sculptor and crochet artist whose work draws deeply from personal, cultural, and ancestral experiences.

- His signature medium combines textile art and broken ceramics, using discarded materials to empower marginalized voices.

- O’Arwisters created Crochet Jam, a participatory art experience rooted in Black quilting traditions and emotional healing.

- His art challenges mainstream art institutions by centering Black, queer, and community-driven narratives.

- Childhood lessons in sewing from his mother and quilting with his grandmother shape his artistic and social practice today.

- Crochet Jam fosters open dialogue on topics like grief, identity, and acceptance, offering safe spaces for expression and connection.

- His recent exhibitions, including A Chorus of Twisted Threads, explore liberation through fabric, form, and community engagement.